Introduction

In the forty-seventh sūra of the Qur’an, Sūrat Muḥammad, God commands, “So know that there is no deity except Allah.”[1] What makes this command especially striking is its timing; it was revealed approximately fifteen years into the Prophet’s mission, at a point when he and his companions already held an unshakable conviction in the oneness of God. Why, then, would such a foundational truth require reaffirmation? The verse suggests that knowing God’s oneness involves more than a one-time acknowledgment; it is an ongoing process that demands sustained reflection, deliberate cultivation, and inner renewal.

Scholars have interpreted this divine command in various ways, many seeing it as a call to seek sacred knowledge, not only about God’s oneness, but also about the broader theological, spiritual, and practical implications of the testimony “There is no deity except Allah” (lā ilāha illā Allāh).[2] This phrase lies at the very heart of Islamic theology. It is the foundational declaration of faith and the essential criterion by which religious belief and practice are measured. The Prophet ﷺ famously described faith as comprising over seventy branches, with the testimony of lā ilāha illā Allāh occupying the highest rank.[3] His teachings emphasize the testimony’s transformative power; true belief in it extends beyond mere intellectual affirmation, fostering profound spiritual conviction and the active cultivation of virtue.

The early ascetic and scholar Sufyān al-Thawrī (d. 161/778) captured this dynamic beautifully when he said, “If certainty (yaqīn) truly fills the heart, it will ascend in yearning for Paradise and trembling in fear of Hellfire.”[4] Some scholars even interpreted the Qur’anic verse, “So by your Lord, We will surely question them all about what they used to do”[5] as an indication that each person will be held accountable for how they upheld the meaning of lā ilāha illā Allāh in their lives.[6]

The theological depth of this declaration has long been affirmed by Muslim scholars. In his widely memorized didactic poem on creed, al-Kharīda al-bahiyya, Aḥmad al-Dardīr (d. 1201/1786), the eminent Egyptian Mālikī jurist and theologian, elucidates that the testimony lā ilāha illā Allāh encompasses the three foundational pillars of Islamic theology: divinity (ilāhiyyāt), prophethood (nubuwwāt), and doctrines known only through revelation (samʿiyyāt).[7] Affirming this testimony entails belief not only in God’s existence, oneness, and perfect attributes, but also—through its complementary declaration, “Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah” (Muḥammad rasūl Allāh)—in the truth of Prophet Muhammad’s prophethood and in the veracity of revealed teachings, including those concerning unseen realities.[8] Hence, this testimony captures the very essence of Islamic creed.

Understanding the full meaning of this testimony is thus indispensable for salvation.[9] Though simple to pronounce and easy to memorize, it functions as a spiritual compass, grounding the believer in the realities of faith. Light on the tongue but weighty on the scales of divine judgment, it dispels doubt and fortifies the heart against Satan’s delusions.[10] As the prominent North African theologian Abū ʿAbdullāh al-Sanūsī (d. 895/1490) notes, when fully comprehended, every tenet of faith becomes a weapon against Satan, and the utterance of “lā ilāha illā Allāh” illuminates and purifies the heart. Though a single phrase in form, it embodies a multitude of convictions, accomplishing in one recitation what might otherwise require prolonged devotion.[11]

This paper offers an overview of the virtues and benefits of the declaration lā ilāha illā Allāh as taught by the Prophet ﷺ and elaborated upon within the Islamic scholarly tradition. It also presents an annotated English translation of selected sections from a fourteenth-century treatise titled Maʿnā lā ilāha illā Allāh (The Meaning of lā ilāha illā Allāh) by the Shāfiʿī jurist and legal theorist Badr al-Dīn al-Zarkashī. The treatise explores the Testimony of Faith from multiple disciplinary perspectives. Sixteen of the original twenty-nine sections were selected for their theological and spiritual significance.[12] Sections focused on technical syntax and complex theological debates were excluded to ensure accessibility and thematic coherence for a general readership.

The majority of the annotations were written by the editor, Yousef Wahb, and the rest by the translator, Tarek Ghanem. The annotations are clearly distinguished from the translated text and appear in the footnotes. They draw upon a wide range of sources—including classical works in theology, grammar, Qur’anic exegesis (tafsīr), and hadith. They are intended to clarify al-Zarkashī’s arguments, provide contextual background, and highlight connections to broader Islamic thought. Care has been taken to preserve the integrity of al-Zarkashī’s voice while offering supplemental insights that support deeper engagement with the text.

On the virtues of lā ilāha illā Allāh

The merits of this declaration are vast and enduring. Throughout history, devout believers have made lā ilāha illā Allāh a cornerstone of their spiritual practice, often committing to its regular invocation as part of disciplined devotional routines. Some are reported to have recited it tens of thousands of times daily.[13] According to accounts drawn from spiritual experiences, some scholars have even reported that uttering this phrase seventy thousand times over the course of one’s life offers protection from the fire of Hell. These reports, while not directly rooted in authenticated prophetic statements, reflect a longstanding belief among scholars in the immense efficacy and transformative power of this testimony. Such traditions underscore the profound spiritual and eschatological significance attributed to lā ilāha illā Allāh, affirming its place as an enduring focus of Muslim devotion, discipline, and hope for salvation.

The names of the testimony

The Qur’an refers to lā ilāha illā Allāh in various contexts, frequently emphasizing its practical and ethical implications. Reports attributed to the companion ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās note that at least nine verses stress either its verbal articulation or the necessity of acting in accordance with its meaning.[14] From these and other passages, scholars identified numerous names for the declaration, each highlighting a distinct facet of its theological and spiritual significance:[15]

- The Word of Unity (kalimat al-tawḥīd): It signifies the absolute negation of all partners with God.

- The Word of Sincerity (kalimat al-ikhlāṣ): Originating in the heart, it reflects pure devotion to God, distinct from all other acts of worship in its exclusive orientation.

- The Word of Perfection (kalimat al-iḥsān): Linked to the verse, “Shall the reward of good (iḥsān) be anything but iḥsān?” (Qur’an 55:60), it teaches that bearing witness to God’s oneness is part and parcel of the believer’s excellence, rewarded with divine protection. Several Qur’anic usages of iḥsān are interpreted as signifying the profession of “lā ilāha illā Allāh.”

- The Prayer of Truth (daʿwat al-ḥaqq): In “The only true prayer is to Him” (Qur’an 13:14), it denotes that after truth there remains only falsehood.

- The Word of Justice (kalimat al-ʿadl): Exegetes explained “God commands justice and good conduct” (Qur’an 16:90) as referring to lā ilāha illā Allāh as justice, and servitude with sincerity as good conduct.

- The Good Speech (al-ṭayyib min al-qawl): In “They were guided to the good speech” (Qur’an 22:24), the “good” was understood as lā ilāha illā Allāh—the most comprehensive good in remembrance and meaning.

- The Pure Word (al-kalima al-ṭayyiba): Likened to a good tree with firm roots and lofty branches (Qur’an 14:24), it signifies a truth deeply rooted in the heart and rising heavenward, pure from distortion or negation.

- The Firm Word (al-qawl al-thābit): God promises to make the believers steadfast with this Word both in this life and the Hereafter (Qur’an 14:27).

- The Word of Righteousness (kalimat al-taqwā): Mentioned in Qur’an 48:26, it serves as the believer’s shield against disbelief.[16]

- The Lasting Word (kalima bāqiya): The legacy left by Abraham for his descendants (Qur’an 43:28), affirming repudiation of idolatry.

- The Word of Steadfastness (kalimat al-istiqāma): As in Qur’an 46:13, those who affirm “Our Lord is God” and remain upright are upheld by it.

- The Supreme Word of God (kalimat Allāh al-ʿulyā): “The Word of God is higher” (Qur’an 9:40). When illumined by it, hearts acquire divine strength, transcending fear of death and worldly desire. Consider Pharaoh’s magicians—once illumined by this Word, they paid no heed to the cutting of hands and feet. Likewise, when the Prophet ﷺ was enraptured by its light, his gaze did not turn toward worldly dominion: “His sight never wavered, nor was it too bold” (Qur’an 53:17).

- The Sublime Similitude (al-mathal al-aʿlā): In “To God belongs the highest similitude” (Qur’an 16:60), it was interpreted as the testimony itself.

- The Covenant (al-mīthāq): In “No one will have power to intercede except for those who have a covenant from the Lord of Mercy” (Qur’an 19:87), the “covenant” was interpreted as the utterance of “lā ilāha illā Allāh.”

- The Keys of the Heavens and the Earth (maqālīd al-samāwāt wa-l-arḍ): These “keys” are understood as none other than the testimony of faith. While shirk rends the cosmos (Qur’an 19:90), tawḥīd restores it. By this Word, the gates of Heaven and the heart itself are opened, while the gates of Hell and satanic whisperings are shut.

- The Word of Truth (kalimat al-ḥaqq): In “None can intercede save those who bear witness to the truth while they know” (Qur’an 43:86), the “truth” refers to this testimony.

- The Firmest Bond (al-ʿurwat al-wuthqā): “Whoever rejects false gods and believes in God has grasped the firmest bond” (Qur’an 2:256), interpreted as lā ilāha illā Allāh.

- The Word of Truthfulness (kalimat al-ṣidq): As in “the one who brings the truth and the one who accepts it” (Qur’an 39:33), it embodies fidelity and affirmation.

- The Common Word (kalimat al-sawāʾ): In “Let us arrive at a statement that is common to us all” (Qur’an 3:64), exegetes understood it as the testimony of divine oneness.

The Qur’an’s instruction to the Israelites to say ḥiṭṭa (“forgive us”) was also interpreted by some exegetes as a call to affirm lā ilāha illā Allāh.[17] While the authenticity of such reports remains debated, the cumulative weight of these interpretations underscores the centrality of the testimony in Islamic theology and practice.

Remembrance

After explaining that lā ilāha illā Allāh encompasses all three domains of Islamic theology, al-Dardīr exhorts:

Hence, diligently recall this phrase with reverence.

Through it, ascend to the loftiest of stations.[18]

Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh al-Sakandarī (d. 709/1309) presents a rich and expansive view of remembrance (dhikr), describing it as the removal of heedlessness and forgetfulness through the heart’s continuous presence with the Divine. At its core, dhikr is the repetition of the name of the One remembered, whether on the tongue or in the heart, but it extends far beyond verbal invocation. It includes the remembrance of God, His attributes, His rulings, and His actions; any reflective thought that draws the soul nearer to Him; and even supplication (duʿāʾ), which arises from the heart’s longing for divine response. The mention of God’s prophets, His righteous servants, or those who strive for nearness to Him, whether through speech, recitation, poetry, teaching, or storytelling, are likewise forms of dhikr.[19]

Remembrance permeates all acts anchored in the Divine: the jurist who seeks God’s judgment, the teacher who imparts sacred knowledge, the mufti who guides hearts, the preacher who kindles souls, and the contemplative who ponders the majesty and signs of God in the heavens and the earth—all are engaged in dhikr. To obey God’s commands and to refrain from what He has forbidden are also forms of remembrance. Dhikr may manifest through the tongue, the heart, or the limbs, and may be performed silently or aloud. When these forms converge, they give rise to what Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh terms “complete remembrance” (dhikr kāmil).[20]

Numerous prophetic traditions underscore the virtues of uttering, understanding, and adhering to lā ilāha illā Allāh. In what follows, a selection of notable hadiths is presented, accompanied by brief commentary.

The best remembrance

The Prophet ﷺ said: “The best thing that I and the prophets before me have said is, ‘There is no god but Allah, alone, without any partner’ (lā ilāha illā Allāh waḥdahu lā sharīka lah).”[21] Al-Tirmidhī’s version includes the addition, “His is the dominion and His is the praise, and He is Able to do all things (lahu al-mulk wa lahu al-ḥamd wa huwa ʿalā kulli shayʾin qadīr).”[22]

In another narration, the Prophet ﷺ also recounts an interaction between Allah and the Prophet Moses, where Moses asked for a special form of remembrance exclusive to him. Allah instructed him to say, “lā ilāha illā Allāh.” Moses responded, “But all Your servants say this.” Allah replied, “Were the seven heavens and their inhabitants, apart from Me, and the seven earths placed on one side of a balance and lā ilāha illā Allāh on the other, the testimony would outweigh them.”[23]

The Prophet ﷺ also said: “The best of remembrance is lā ilāha illā Allāh and the finest supplication (duʿāʾ) is praise of Allah (al-ḥamd lillāh)”[24] and “Glorifying Allah (tasbīḥ) fills half the scale, praise of Allah (al-ḥamd lillāh) fills the entire scale, and lā ilāha illā Allāh has no veil between it and Allah until it reaches Him.”[25]

The testimony of faith, lā ilāha illā Allāh, stands unparalleled in the practice of remembrance, for it encapsulates the very essence of faith. God mentions it in His Book thirty-seven times, and every act of worship reflects its meaning. In purification (ṭahāra), one negates impurity and affirms purity. In almsgiving (zakat), one negates attachment to wealth and affirms love of God, manifesting detachment from the world and reliance upon Him alone. Likewise, since the heart is crowded with other-than-God, the word of negation must first expel these intrusions; once emptied, “the pulpit of divine oneness is established within, upon which sits the sovereign of gnosis.”[26]

The hadiths above affirm lā ilāha illā Allāh as the most excellent form of remembrance. What is set forth in universal terms must necessarily be of the loftiest realities and the weightiest in worth—for it stands in opposition to numerous false claims and beliefs, and thus requires a power sufficient to overcome them all.[27] This distinction reflects broader hierarchies within the Islamic tradition: Just as the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ is regarded as the most excellent of creation, and certain angels—such as Jibrīl—are considered the foremost of their kind, particular phrases likewise hold preeminence within devotional categories. Thus, while al-ḥamd lillāh is considered the most excellent expression of gratitude and supplication, lā ilāha illā Allāh remains the supreme remembrance.[28]

The phrase “al-ḥamd lillāh” is esteemed as an ideal supplication because it expresses both praise and gratitude, which are intimately tied to God’s mercy and benevolence. While supplication generally involves requesting something from God, al-ḥamd lillāh implicitly conveys this supplicatory aspect through its exaltation of the Divine. Nonetheless, the excellence of al-ḥamd lillāh as a supplication does not diminish the superior status of lā ilāha illā Allāh as the highest form of remembrance. Supplication constitutes one aspect of remembrance, but dhikr encompasses a broader spectrum of devotional acts, including glorification (tasbīḥ), praise, and above all, the affirmation of divine unity.

Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh mentions that, as the supreme form of remembrance, the Testimony served as a source of refuge and deliverance for both God’s friends and adversaries in moments of extreme distress. Consider the examples of Pharaoh and of the Prophet Jonah (Yūnus): Pharaoh uttered the Testimony while drowning, and Jonah proclaimed it from within the belly of the whale. Yet only Jonah’s declaration was accepted, as it reflected a prior, sincere commitment to God. God Himself testifies: “Had he not been of those who exalt Allah, he would have remained inside its belly until the Day they are resurrected.”[29] Pharaoh, in contrast, pronounced the words with an absent heart; his utterance arose not from submission and conviction but from the desperate desire to save himself from death.[30]

Daily recitation and its rewards

The Prophet ﷺ said: “Whoever recites the following a hundred times a day: ‘lā ilāha illā Allāh waḥdahu lā sharīka lah lahu al-mulk wa lahu al-ḥamd wa huwa ʿalā kulli shayʾin qadīr,’ will receive a reward equivalent to freeing ten slaves, a hundred good deeds will be recorded for them, a hundred sins will be erased, and they will be safeguarded from Satan for that day until evening. No one will surpass them in good deeds except those who recite it more.”[31]

He ﷺ also said: “Whoever says: ‘lā ilāha illā Allāh,’ it will benefit them one day [on the Day of Judgment], even if it is after they endure punishment”[32] and “No servant has ever uttered ‘lā ilāha illa Allāh’ sincerely, except that the gates of Heaven are opened for it, until it reaches the Throne, so long as the person avoids major sins.”[33]

The proclamation of the Testimony is perhaps the only act of worship that God has both obligated and joined us in performing, “Allah [Himself] bears witness: ‘There is no deity except Him,’ and so do the angels and those endowed with knowledge, affirming that He sustains creation in perfect justice: ‘There is no deity except Him, the Exalted in Might, the Wise.’”[34] The repetition of the phrase within the verse underscores the necessity of continual remembrance; one is enjoined to proclaim it throughout the entirety of life.[35]

One should remember Allah with full strength and reverence, intending with “lā ilāha” to remove from the heart all that is other than God, and with “illā Allāh” to establish His presence within it, so that His remembrance permeates one’s entire being. Each utterance should be accompanied by mindful presence.

Some scholars held that dhikr is only complete if each repetition conveys a fresh meaning. The lowest degree is that, with every “lā ilāha illā Allāh,” the heart contains nothing besides God; if, during remembrance, the heart turns elsewhere, that object is effectively treated as a god. The Qur’an warns: “Have you seen the one who takes his own desire as his god?”[36] and “Did I not enjoin upon you, O children of Adam, not to worship Satan?”[37] Likewise, the Prophet ﷺ said: “Perish the slave of the dinar, perish the slave of the dirham”[38]—not for bowing to gold or silver, but for attaching the heart to them. If the heart is crowded with sensory images, a thousand utterances may pass without meaning; but when emptied of all besides God, even a single “Allah” can yield an indescribable delight. While lā ilāha illā Allāh is the essence of spiritual orientation, it is also the key to the heart’s realities and the ascent of seekers toward the unseen.[39]

On the etiquette of this dhikr, some recommend flowing seamlessly from “lā ilāha” to “illā Allāh” without outward or inward pause, to deny Satan any opening since this can more swiftly open the heart and draw one nearer to the Lord. Others prefer elongating the phrase, so that during “lā ilāha” all rivals to God are recalled and negated, and with “illā Allāh” divine oneness is affirmed. Still others avoid elongation, lest death arrive before reaching the final affirmation.[40]

This concern for cultivating spiritual presence extends into the Qur’anic sciences of tajwīd and qirāʾāt, where reciters recommend madd al-taʿẓīm: intentionally lengthening the phrase “lā ilāha illā Allāh” (and similar Qur’anic formulations) to four counts, even for those whose usual recitation is shortening (qaṣr). Unlike the standard phonetic causes for elongation, such as the meeting of a hamza or sukūn, madd al-taʿẓīm is driven by a semantic aim: to intensify the negation of all divinity besides God and magnify His exclusive lordship.[41] Ibn Mihrān (d. 381/991) explains that it is called the “elongation of emphasis” because it heightens this negation, a practice well known among the Arabs in supplication, seeking aid, and emphatic denial, even in words without an etymological cause for elongation, and all the more in those that have one.[42] Al-Nawawī, in al-Adhkār, likewise praised prolonging “lā ilāha illā Allāh,” citing its deep roots in the practice of “the early and later generations” and its power to foster attentiveness and contemplation.[43] Thus, the measured elongation of lā becomes not only a refinement of tajwīd but a devotional act, embodying in the reciter’s breath the expansiveness of negation before the fullness of divine affirmation.

Regarding the role of lā ilāha illā Allāh in expiating sins, scholars have debated its scope. Many hold that its recitation primarily atones for minor transgressions,[44] while others interpret hadiths indicating that sincere proclamation can, in some cases, protect one from the Hellfire, suggesting that its effect may extend even to major sins.[45] Nonetheless, the complete expiation of major sins requires repentance and the rectification of any violated rights. Yet, through the blessing of lā ilāha illā Allāh, Allah may soften hearts, inspiring reconciliation and forgiveness among people, thereby opening a path toward a more comprehensive divine pardon.[46]

Legal status and communal consequences

The Prophet ﷺ said: “I have been commanded to fight against people until they declare ‘lā ilāha illa Allāh.’ If they profess it, their lives and property are granted protection, except where justified [by law], and their ultimate reckoning is with Allah.”[47]

Faith is first rooted in knowledge within the heart, which constitutes its essential core: “Know that there is no deity except Allah.” This inner recognition must then be expressed through verbal affirmation: “Say: He is God the One.”[48] The imperative “say” obliges the believer to articulate with the tongue that which signifies tawḥīd, for faith carries both inward and outward consequences. Its inward aspect, hidden in the heart, pertains to the afterlife, while its outward aspect governs worldly duties and social obligations, which can only be recognized through speech. Without verbal acknowledgment, one’s status as a believer cannot be externally confirmed, nor can the attendant legal and social obligations be properly enforced. Knowledge constitutes the essential pillar of faith before God, while verbal declaration serves as its legal and social pillar—necessary for the recognition of obligations and rights, as indicated in Allah’s command: “Do not marry polytheistic women until they believe.”[49]

This hadith illustrates that the Testimony of Faith constitutes the minimal threshold for entering the fold of Islam. It delineates the lowest of five ascending degrees of commitment, whereby mere verbal utterance secures the legal protection of life and property. This level includes both sincere believers and hypocrites. Its virtue is such that anyone who attaches themselves to the statement partakes in its blessings: those seeking the hereafter are granted the felicity of both abodes.

Beyond this foundational level, Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh outlines four higher degrees of realization. The second pertains to those who combine verbal affirmation with inner conviction, even by way of imitation (taqlīd). The third adds intellectual comprehension through knowledge of rational proofs underlying belief. The fourth ascends to certitude rooted in definitive evidence. The fifth and highest station is reserved for those graced with spiritual witnessing (mushāhadāt) and divine manifestations (tajalliyāt), where the veils are lifted and faith becomes grounded in direct experiential knowledge.[50]

Salvation and intercession in the Afterlife

The Prophet ﷺ said: “No soul dies bearing witness to lā ilāha illā Allāh and that I am the Messenger of Allah with sincere conviction, except that Allah forgives it.”[51] He also stated: “He who dies while certain of lā ilāha illā Allāh will enter Paradise,”[52] “If anyone’s last words are ‘lā ilāha illā Allāh,’ they will enter Paradise,”[53] and “If anyone comes on the Day of Resurrection having said ‘lā ilāha illā Allāh’ sincerely, with the intention of seeking Allah’s pleasure, Allah will forbid the Hellfire from touching him.”[54]

When asked, “Who will be the most fortunate person to receive your intercession on the Day of Resurrection?” The Prophet ﷺ replied, “The most fortunate person to receive my intercession will be the one who sincerely and wholeheartedly declared, ‘lā ilāha illā Allāh.’”[55] At the deathbed of his uncle Abū Ṭālib, the Prophet ﷺ urged him, “O my uncle! Say ‘lā ilāha illa Allāh,’ a phrase [that will cause me to] intercede for you before Allah.”[56]

When uttered at the moment of death—after desires have faded, the rebellious self has softened, and one surrenders fully to the power of God—the testimony arises with sincerity, the outer and inner selves brought into harmony. Such a testimony, spoken in purity and truth, becomes a cause for forgiveness. By contrast, when recited in health, the Testimony is often mingled with distraction, as the heart remains laden with attachments and restless desires. The human soul is easily ensnared by passion, intoxicated with the world, and heedless of the hereafter, leaving little room for true certainty (yaqīn). Only when certainty becomes firmly rooted in the heart does it radiate as a light of divine recognition—and death is a moment when such yaqīn often crystallizes.

At the same time, the prophetic traditions should not be read in a narrowly literal sense. Many scholars explained that “last words” refers not only to a final utterance at the point of death but also to a life consistently lived in fidelity to lā ilāha illā Allāh. In this broader sense, one whose entire existence bears witness to divine oneness may be counted among those whose “last words” were the testimony of faith, even if not physically spoken in their final breath.[57]

Encouraging the dying (talqīn) to recite it

The Prophet ﷺ said: “Exhort your dying ones to recite: ‘lā ilāha illā Allah.’”[58]

As mentioned above, for the Testimony to be salvific, it must be uttered with certainty, and certainty arises only when worldly desires have been subdued. This may happen in one of two ways: either through lifelong self-discipline that tames the passions, or at the time of death, when hope and fear of God are heightened and the dying person’s attention is turned away from all else. In that state, pronouncing the Testimony secures forgiveness.[59] At that decisive moment—when the soul trembles at the threshold of departure—the intricate details of doctrine may slip beyond reach, leaving only what the heart has genuinely internalized. Through steadfast remembrance and mindful reflection, the believer trains the soul to summon lā ilāha illā Allāh with clarity and confidence when the veils of this world are lifted, sealing one’s life with the ultimate affirmation of truth.[60]

On this basis, prompting the dying to say the Testimony (talqīn) is unanimously regarded as Sunnah, as it helps fix the heart and tongue upon the word of tawḥīd in life’s final moments. Jurists, however, differ over extending talqīn to after burial: some uphold it as a valid tradition, intended to remind the deceased of faith and reaffirm their bond with the Testimony even in the grave.[61]

The card of testimony

The Prophet ﷺ said: “On the Day of Judgment, Allah will single out a man from my community before all of creation. Ninety-nine scrolls [of sins] will be laid out for him, each extending as far as the eye can see. Allah will ask him: ‘Do you deny any of this? Have My recorders wronged you?’ He will reply: ‘No, O Lord!’ Allah will ask: ‘Do you have an excuse?’ He will reply: ‘No, O Lord!’ Then He will say: ‘You have one good deed with Us, and you will not be wronged today.’ A card (biṭāqa) will be brought forth, inscribed with: ‘I testify that lā ilāha illā Allāh, and I testify that Muhammad is His servant and Messenger.’ Allah will then command: ‘Bring the scales.’ The man will say: ‘O Lord! What is this card compared to these scrolls?’ Allah will respond: ‘You shall not be wronged.’ The scrolls will be placed on one side of the scale, and the card on the other. The scrolls will become light, and the card will outweigh them, for nothing outweighs the name of Allah.”[62]

The weight of lā ilāha illā Allāh is truly appreciated only by those who grasp its measure. It is a phrase of divine unity, unmatched and unopposable; were anything able to counter it, it would no longer be singular but dual, and so forth. Only its opposite—polytheism—can oppose it, and there is nothing genuinely equivalent. A person is either a monotheist or a polytheist; both cannot coexist on the scale.[63]

This hadith inspires a profound sense of hope in Allah’s boundless mercy, emphasizing the transformative power of steadfast adherence to the essence of lā ilāha illā Allāh. Scholars have debated whether the “card” mentioned in this narration symbolizes the minimal level of adherence to lā ilāha illā Allāh required for one to be considered a Muslim. Some argued that such minimal affirmation negates disbelief but does not guarantee full conformity with the tenets of faith or a life of righteous conduct.[64] Indeed, the scale does not tip merely through verbal utterance: if it did, all who pronounce tawḥīd would automatically be saved from Hell. Rather, God intends that the merit of this affirmation be revealed in its proper measure. Those who enter Hell despite uttering tawḥīd remain there until, through intercession or divine grace, they are brought out.

Furthermore, some scholars have suggested that deeds, though metaphorically represented by scales on the Day of Judgment, persist in tangible forms in the Afterlife. These righteous actions are preserved within the dwellings of Paradise, serving as perpetual sources of joy and consolation for the believer, offering both a reminder of Allah’s mercy and a reflection of their own efforts in this world.[65]

On the benefits of the testimony of faith

The declaration lā ilāha illā Allāh brings about an ever-growing connection with the transcendent, all-powerful, infinite, and perfect divine reality. Embracing this reality leads to profound transformation—spiritual, emotional, psychological, and existential—grounded in the certainty and clarity it imparts. Delving into its deeper meanings reveals not only theological, linguistic, and rhetorical insights—as we will soon see Imam al-Zarkashī so masterfully demonstrate—but also unveils indescribable spiritual benefits accessible through consistent and intentional invocation. Al-Sanūsī offers particularly insightful reflections on these benefits in his theological primer Umm al-barāhīn. He categorizes them into two primary types. The first pertains to righteous virtues, which he enumerates as follows:

- Detachment from worldly attachments (zuhd).

- Freedom of the heart from reliance on fleeting matters.

- Reliance (tawakkul) on Allah.

- Conscientious shame (ḥayāʾ), defined by al-Sanūsī as, “Glorifying Allah, the Mighty and Majestic, through constant invocation of Him, adherence to His prohibitions, and refraining from voicing complaints about Him to needy and powerless beings.”

- Spiritual sufficiency (ghinā), characterized by resilience in faith even when facing material deprivation.

- Absolute neediness (faqr) directed to Allah alone.

- Altruism (ithār), practiced in a way that remains praiseworthy and consistent with the dictates of sharīʿa.

- Chivalry (futuwwa).

- Gratitude (shukr), defined as directing the heart wholly towards praising Allah and recognizing His blessings, even when they are concealed within trials and tribulations.[66]

To further elaborate on zuhd—one of the most fundamental of these benefits—the Egyptian Mālikī jurist and theologian Muḥammad al-Dasūqī (d. 1230/1815) defines it as detachment from:

…those things that people take pride in, such as food, drink, and clothing. If a person possesses wealth, they pay it no heed and do not cling to its preservation; rather, they spend it [rightfully], and if it is lost, they are not distressed by it… Zuhd does not contradict possessing abundant wealth, for what matters is the inner detachment of the heart from inclination toward it, whether it is in one’s possession or not.[67]

Al-Sanūsī’s second category of benefits pertains to extraordinary divine favors (karāmāt) that Allah bestows upon His pious servants (other than prophets) as a result of their sincere declaration and steadfast commitment to lā ilāha illā Allāh. These manifestations may include occurrences such as Allah placing immense blessing in a pious person’s food, allowing it to suffice for many. However, al-Sanūsī cautions that the believer should not pursue such miraculous outcomes through acts of worship, as doing so risks falling into concealed polytheism (shirk khafy) and becoming vulnerable to divine retribution.[68] Instead, the believer is encouraged to engage in the remembrance of lā ilāha illā Allāh with a purified heart, detached from all but Allah and fully focused on Him. Al-Sanūsī emphasizes that the believer’s sole intention should be “the good pleasure of their Lord, who has no substitute and from whose need no one is independent.”[69]

Imam al-Zarkashī and his book Maʿnā lā ilāha illā Allāh

Two key aspects of al-Zarkashī’s life are particularly relevant to understanding his scholarship: his exceptional erudition and his profound piety. Born in Mamluk Cairo in 745/1344, Abū ʿAbdullāh Badr al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn ʿAbdullāh ibn Bahādur al-Zarkashī was of Turkish descent. His epithet, al-Zarkashī, derives from his early involvement in embroidery (zarkash), his father’s trade. He was also known as al-Minhājī due to his memorization of al-Nawawī’s seminal Shāfiʿī legal manual, al-Minhāj.

Al-Zarkashī’s scholarly journey took him to some of the most renowned centers of learning of his time. In Damascus, he studied hadith with eminent scholars, such as Ibn Kathīr (d. 774/1373) and Ibn Qudāma al-Maqdisī (d. 780/1379). He pursued advanced legal studies in Aleppo under Shihāb al-Dīn al-Adhraʿī (d. 783/1381) and later refined his expertise in Cairo under prominent figures, including Jamāl al-Dīn al-Isnawī (d. 772/1370), head of the Shāfiʿī school Sirāj al-Dīn al-Bulqīnī (d. 805/1403), and ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Mughulṭāy (d. 762/1361).

After completing his studies, al-Zarkashī settled in Egypt, dedicating himself to teaching, writing, and issuing legal opinions (fatwas). He served as dean at Karīm al-Dīn’s Khanqah (Sufi lodge) in the Cairo Necropolis, located in the smaller Qarafa beneath the Mokattam Hills. The historian Ibn Taghrībirdī (d. 874/1470) described him as:

Excelling in law and many other disciplines, he played a significant role in teaching and issuing fatwas. He authored commentaries, abridgments, and compilations in his own handwriting. He avoided positions of power, wore modest clothing even when attending gatherings or visiting the markets. He was known for his humility and aversion to ostentation.[70]

Al-Zarkashī’s influence extended through his students, many of whom became leading scholars in their own right, such as Shams al-Dīn al-Birmāwī (d. 831/1427), the Damascene judge Najm al-Dīn ʿUmar ibn Ḥajjī (d. 830/1427), and the Alexandrian Mālikī jurist Muḥammad ibn Ḥasan al-Shumanī (d. 821/1418). Though engaged in public teaching, al-Zarkashī was known for his reserved nature and preference for seclusion. He often retreated to bookstores, where he read and meticulously annotated texts—notes which formed the basis of his prolific scholarly output.[71]

Despite his relatively short life, passing at the age of 49, al-Zarkashī authored numerous influential works across disciplines such as hadith, law, Qur’anic studies, theology, logic, and literature.[72] His intellectual contributions were widely recognized. His al-Burhān fī ʿulūm al-Qurʾān was one of the first comprehensive works on Qur’anic sciences and later became a key source for al-Suyūṭī’s al-Itqān.[73] His magnum opus, al-Baḥr al-muḥīṭ, remains unparalleled in the field of legal theory for its exhaustive treatment of legal methodologies and juristic reasoning, remarkably completed when he was only 32.

Al-Zarkashī lived a life of scholarly devotion and spiritual discipline. He avoided public recognition, often locking himself in a room in Cairo’s bustling book market to read and take notes, pausing only for prayer. At night, he compiled his annotations into manuscripts and engaged in worship. He died on 3 Rajab 794/27 May 1392 and was buried in the smaller Qarafa cemetery near the tomb of Amir Baktamur al-Sāqī. His intellectual legacy lives on through his writings and the many students he mentored.

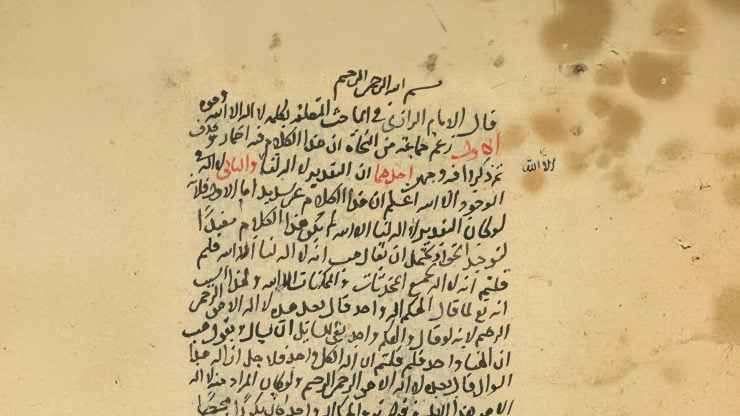

Among al-Zarkashī’s many contributions is his short yet profound treatise Maʿnā lā ilāha illā Allāh. According to the introduction, al-Zarkashī composed it in a single night, dividing it into 29 sections that examine the grammatical, rhetorical, legal, theological, logical, and spiritual dimensions of the statement. The treatise begins with a syntactic analysis of the phrase, examining the implications of the negation particle (lā) and the word order. Al-Zarkashī comments on its phonetic properties, noting that the letters used to compose the phrase are articulated from the oral cavity (jawf) and throat and are undotted—a feature he associates with specific spiritual qualities. He then compares lā ilāha illā Allāh with other Qur’anic statements denying the existence of any deity besides Allah, demonstrating the phrase’s unique theological significance. He also explores the etymology and meanings of the divine name “Allah,” delving into the relationship between the name and the divine attributes.

Note on the translation and annotation

The translation in this paper is based on the third edition of Maʿnā lā ilāha illā Allāh, published by Dār al-Iʿtiṣām in 1985 and edited by ʿAlī al-Qaradāghī. Since the publication of this edition, several sources cited by al-Qaradāghī—once accessible only in manuscript form—have become available in modern editions. These include Muḥyī al-Dīn al-Kafiyajī’s (d. 879/1474) seminal treatise, al-Anwār fī ʿilm al-tawḥīd: sharḥ kalimatay al-shahāda. Additionally, select unpublished texts were consulted, such as a concise treatise by Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (d. 606/1210) that examines the linguistic dimensions of lā ilāha illā Allāh, and informed the annotations presented in this study. Al-Qaradāghī’s own editorial notes were likewise useful and are engaged throughout.

The sixteen sections selected for translation delve into the semantic and syntactic intricacies of the Testimony of Faith. Among the topics examined are the significance of definite and indefinite forms, the implications of singular and plural constructions, the dialectic relationship between negation and affirmation, and the universal scope embedded in the testimony’s formulation. The text also explores the acoustic resonance and theological weight of the majestic name Allah, alongside other divine names. To aid clarity and reader engagement, thematic subsection headings have been introduced throughout the translation.

By rendering its rich insights into English, we aim to offer readers not only conceptual and theological depth, but also a pathway to cultivating a more intimate connection with the essence of tawḥīd. At its heart, the testimony of faith serves as both a doctrinal cornerstone and lived expression of divine oneness.

Throughout the translation process, readability and conceptual clarity in idiomatic English have been prioritized over rigid literalism, in order to better convey the intended meanings of the original work.

Annotated Translation of Selected Sections from Maʿnā lā ilāha illā Allāh

Introduction

In the name of Allah Most Merciful, Most Compassionate

May peace and blessings be upon our Master Muhammad, his family, and companions. Praise be to Allah, in a way commensurate with His blessings and befitting of His largesse. May peace and blessings be upon our Master Muhammad—the one with virtuous characteristics—his family, and companions as long as time goes on, be it short or long.

What follows is a collection of beneficial notes, gems for the ones with high resolve. Related to the testimony “There is no deity but Allah” (lā ilāha illā Allāh),[74] most of them are innovative, rare, and offered free of charge. I wrote it on a night consumed by the influence of groundbreaking ideas and the unfolding of contemplation. My only companions were an inkstand and a lamp, and my closest company was the raging fire of my thoughts, swirling with intensity and chaos. This continued until the morning broke with a joyous announcement, ushering the most virtuous of innovations. With this, I traveled from the realm of thought to that of insight, seeking the forgiveness of the Exalted and Most-Forgiving.

I arranged the work into chapters.[75]

5. The underlying semantic structure of the testimony of faith

The phrase lā ilāha illā Allāh is understood by most scholars to have an omitted predicate (khabar) [a missing word or idea that’s implied but not directly stated]. Some suggest the missing part is the word “existent” (mawjūd), others say “for us” (lanā), and some say “in truth” (bi-ḥaqq).[76] This is because false gods—like idols—exist in reality, and the intended negation is of everything other than the True God.[77] Some scholars disagree and deny the need for an implied word, arguing that denying any god—or negating the essence (māhiyya)—without restriction is more comprehensive than negating it with a restriction. However, assuming an implicit word is preferable and consistent with Arabic linguistic norms regarding the omission of predicates [where sometimes parts of a sentence are understood without being said]. Based on this, the best interpretation is that the phrase means: “There is no god, in truth, except Allah.” This way, the phrase comprehensively affirms what cannot be negated (the one true God) and negates what cannot be affirmed (all false gods).[78]

7. Affirmation takes precedence over negation

Some theologians (mutakallimūn) uphold that it’s more fundamental and necessary to understand that affirmation takes precedence over conceptualizing negation. This is because you can picture the possibility of something existing without first thinking about its absence, but you can’t fully grasp what’s being denied unless you already have an idea of what’s being affirmed.[79] So then, why does the Testimony of Faith begin with a negation (“There is no god”) before moving to an affirmation (“except Allah”)?

They respond by highlighting that negating or denying necessity (wujūbiyya) for everything except Allah and then affirming it for Him, the Most High, is a stronger assertion than simply affirming it.

Experts in the art of rhetoric (ahl al-maʿānī) hold that the Testimony of Faith starts with a negation because a negation clears the heart. If the heart is vacant, the manifestation of God’s oneness (tawḥīd) is more likely to occur, as well as the illumination of Allah’s light upon it.

Similarly, some scholars also say that the Testimony of Faith begins with a negation to purify the heart from anything other than God (aghyār), polishing its essence and allowing light, hidden truths, and deep insight to appear. This implication mirrors Sufi gnosis and is more fitting to reflect meanings related to lordly secrets.[80]

8. Two special acoustic features

The statement “lā ilāha illā Allāh” contains two distinct acoustic characteristics. First, all its letters are pronounced with hollow sound articulation (from the oral cavity, or jawfiyya), not containing letters pronounced using the lips (lip sounds, or shafahiyya). This symbolizes that the words come from deep within—from the heart, not just the lips. Second, it contains no dotted (muʿjam) letters; all of them are dotless, symbolizing a detachment from anything worshiped other than Allah, the Most High.

9. Allocation and exclusivity (ḥaṣr) of true Godship

The statement lā ilāha illā Allāh, in this particular formula, synthesizes negation and affirmation to signify the exclusiveness (ḥaṣr) of divinity to Allah, the Most High.[81] Combining negation and affirmation is one of the most articulate formulas by which to define something, clearly setting boundaries or limits around it.[82] It has been established that this noble statement is sufficient in affirming unicity to Allah, the Most High, without needing to explore if there is an intermediary between the negation and affirmation, or adding any other word to it.

However, is the meaning of this affirmation assigned by linguistic convention (waḍʿ) or divine revelation? Or does it indicate a negation of any shared deity?

Affirming divinity for Allah, the Most High, is something naturally known by every rational person. For proponents of this opinion, affirmation means affirming a commendable attribute of Allah, the Most High. Others claim that this affirmation is based on both context and scripture. The contextual evidence is that the messages brought by the messengers clearly call people to affirm God’s unicity. This context shows that when someone says the Testimony of Faith, they intend this meaning. This supports the view that excluding something from a negation is not itself an affirmation, and that utterances are meant to signify ideas in the mind, not extramental propositions.[83] In fact, the reason this venerated statement is directed to those who are religiously responsible (mukallafūn, sing. mukallaf), making them accountable for it, is to affirm the divinity of Allah, the Most High, alone. The Lawgiver [i.e., the Prophet], Allah’s peace and blessing be upon him, was satisfied with this statement on its own, without needing any added words.[84]

If this statement did not signify tawḥīd, then it would have needed additional clarification—because tawḥīd is the original intent of every messenger’s mission. Also, there is a consensus of specialists and non-specialists, from the earliest to the later generations, that it affirms tawḥīd, which is why they called it the Statement of God’s Oneness (kalimat al-tawḥīd). Claiming that something must supplement the statement confuses the message of the Sacred Law (sharʿ), using dialectical terminologies that are neither worthy of consideration nor permissible.

Furthermore, the absence of any word between “no” (lā) and “except” (illā) shows that it is a categorical negation, signifying the negation of the existence of every deity. Then, the word “except” (illā) immediately affirms the opposite: that divinity belongs to Allah, the Most High. This meaning is clear and straightforward.

A poet versified,

Nothing is correct in the minds,

If there is ever a need to prove the daybreak!

10. On the difference between the two statements: “Lā ilāha illā Allāh” and “Mā min ilāh illā Allāh”

Al-Zamakhsharī (d. 538/1144) equates the statements “There is no deity but Allah” (lā ilāha illā Allāh) and “Other than Allah, there is no deity” (mā min ilāh illā Allāh) because both statements contain negation and affirmation. Min [a particle used here to emphasize total negation, often called a partitive or symbol of clarification] explicitly affirms comprehensive negation (nafy mustaghriq) in one of the two sentences, while in the other statement, this meaning is understood implicitly.

It appears that lā ilāha illā Allāh is more articulate, which is why it was the most commonly chosen form. This is because lā is more conventionally established in Arabic for expressing general negation than mā. Notice how lā negates the very essence of something, as proven by the omission of its object (khabar)—often as a way of proclaiming that the intent is on the subject (ism), not the object. Since the Statement of Unicity is meant to deny the very existence of a god other than Allah, using lā is more fitting to its established linguistic usage.

Furthermore, if the preposition min is omitted and its meaning included within the noun used with lā, the phrase becomes more articulate. This is because implying the meaning directly in the noun (taḍmīn) makes it comprehensive. A noun also carries a stronger connotation than a preposition, and the added structure creates an addition in meaning that was not there before.

11. Signifying categorical inclusion (istighrāq) by singular words (god) instead of plural words (gods)

The sense of comprehensiveness or total exclusion/inclusion (istighrāq) expressed by a singular (mufrad) word is stronger than when using its plural (jamʿ). For example, it is appropriate to say “No men are in the house” (lā rijāl fī al-dār) if there are two or three men in the house. However, it would not be appropriate to say, in this scenario, “No man is in the house…” (lā rajul fī al-dār), as it would be understood that not a single man is in the house.

As such, this demonstrates the subtlety of Allah’s words, the Most High. Discussing the call of Prophet Zechariah (Zakariyyā), peace be upon him, who said “Lord, my bone [ʿaẓm] has weakened” and did not say “bones” (ʿiẓām), al-Zamakhsharī said,

He used the singular form “ʿaẓm” because a singular noun connotes a broad group (or category) that shares common features, otherwise known as a genus. What he [Prophet Zakariyyā] means is that this group, which serves as the pillar upon which the body relies, is afflicted with fragility. Had the plural been used, the interpretation would have shifted to a different meaning. That is, that not just some of his bones had become fragile, but rather all of them had.

The Imam of the Two Sanctuaries (Imām al-Ḥaramayn) [al-Juwaynī] (d. 478/1085), stated in al-Burhān,

Here is a matter that an examiner should be aware of. That is, the word al-tamr (lit. the date) is more likely to encompass the genus than al-tumūr (the dates), but not based on the wording itself. The word al-tumūr prompts the listener to first visualize individual dates, then visualize them as a collective group, as indicated by the plural form.[85]

The commentators [i.e., of al-Burhān] said that al-Juwaynī meant that someone seeking to refer to the category as a whole would use tamr, which pertains to the collective entirety. In contrast, tumār refers to multiple individual entities. As such, it describes the individual components, not the totality.

Once you know this, the subtlety of negating the singular in the Testimony of Faith will not be wasted on you.

12. The implication of using “ilāh” as an indefinite word in the context of negation

In the Testimony of Faith, the word “deity” (ilāh) is used in an indefinite form within a statement of negation, which undoubtedly gives it a general meaning. So then, what is meant by the [expert’s] statement that if the indefinite is within a statement of general negation, it is not absolute? Litterateurs and legal theorists agree that when we say, “There is no man at home” (lā rajulun fī al-dār) [using a nominative (rafʿ) case; i.e., rajulun], it does not indicate a general meaning. Instead, it should be said ‘‘There is no man but two at home” (lā rajulun fī al-dār bal ithnān), even though it is indefinite in a negative context. Also, people agree that the statements, “Not every animal is human” (laysa kull ḥayawān insān) and “Not every number is even” (laysa kull ʿadad zawj) are true, but not general in meaning, even though they contain indefinites within a negative statement.

The disagreement cannot be resolved by arguing that an indefinite noun paired with lā always indicates total negation because we also say, “No one came to you” (mā jāʾaka min aḥad) and “There is no one in the house” (laysa fī al-dār aḥad), which express comprehensiveness without using lā. Hence, this point of dispute remains problematic.

The answer is that when an indefinite word is used in a negative sentence, it typically implies the denial is general and comprehensive—except in these two instances. The reason for this exception is clear. In the first case, the intention is to negate a general concept [what scholars call a universal quiddity, meaning the essence that something shares with others of its kind; māhiyya kulliyya], without making impossible the qualification of uniqueness (wiḥda) in individual examples. That’s why it makes perfect sense to say, “There is no man in the house but two.” However, the meaning changes when the indefinite word is paired with lā. In this case, it typically serves as a reply to someone asking “Is there a man in the house?” and the response “There is no man in the house” means that none of the individuals from that category are present in the house.

The inclusion of min is what causes the subject to be fixed in grammatical form (non-inflected or bināʾ), as mentioned earlier. But in this case, when the assumed meaning no longer includes min, the cause for that grammatical fix no longer applies. Therefore, the sentence is considered a new declarative statement (ikhbār mustaʾnaf), rather than a response (jawāb).

As for the second case, it refers to the negation (salb) of the predication from general categories only. The verification (taqrīr) of the matter is as follows: someone claiming, “Every number is even.” In saying this, they affirm a general predication—applying evenness to all numbers. Now, we want to challenge this kind of universal affirmative proposition (mujība kulliyya). To do so, it is enough to suspend the predication on just one of the individuals to suspend a universal affirmative. That’s because proving a single exception is enough to disprove a universal claim. That is why a negative particular statement (saying that at least one case doesn’t fit) is considered the contradictory (naqīḍ) of a universal affirmative—we’re not denying the statement applies to all individual cases, but rather, we’re rejecting that it applies to all of them without exception (the predication of universality itself). Therefore, when we say that an indefinite noun indicates generality, this applies only when the negation is applied to all individual members of that category. It does not apply when the negation concerns only some of the individuals—this is called a negative particular statement.

14. & 15. The implication of negating the indefinite word, “ilāh”

A negated indefinite [proposition], as in the Testimony of Faith, is stronger in conveying generality than simply placing an indefinite word in a negative sentence. This is why Sayf al-Dīn al-Āmidī (d. 630/1233) said in Abkār al-afkār, “An indefinite word in a negative context is not generalized. Rather, a negative indefinite itself is generalized.”[86]

If you understand this, then you’ll also understand that an indefinite word in a positive, affirmative statement does not imply generality, according to what a group of legal theorists have declared. However, the reality of the matter is different from that, and depends on the specific context.

Here, I intend to demonstrate that there is an exception for two forms:

- First, if this is a conditional context (siyāq al-sharṭ), as noted by the Imam [al-Juwaynī] in al-Burhān; and

- Second, if it is in a context of gratitude (siyāq al-imtinān), as stated by Judge Abū al-Ṭayyib al-Ṭabarī (d. 450/1058).

17. The unique proper name “Allah”

The name Allah is a proper name (ism ʿalam) that is necessary and unique to His essence, the Most High. Allah did not let anyone other than Him share in saying it as a name, just as no one shares in its meaning. The same applies to His divine attributes. The name Allah is like other proper names in that it can be described but cannot be used to describe other objects—it is a name only for Him, just as other proper names are assigned to things other than Allah.[87] However, in principle, proper names are made as a convention to differentiate between those with names, which is an impossibility for Allah. This name also stands as an exception to disagreement over which of the two types of definites is more known.[88] It is for this reason that Sībawayh said, “The name of Allah, Most High, is the most definite of all definite nouns (aʿraf al-maʿārif).” It is narrated that Sībawayh was seen in a dream having been given an abundance of goodness as a reward for this statement.

18. The name “Allah” is a proper noun that is not derived from anything

The majority of scholars hold that the name of Allah, the Most High, is like a proper name that is not derived from any other word.[89] They cite the Qur’anic verse, “Do you know of any namesake for Him?” as proof.[90] They hold that Allah would have a namesake if the word were derived, just as the polytheists called their idols “gods” (āliha, singular ilāh). But this connection is not necessary because what the polytheists called idols is what Allah, Most High, narrates as saying, “They said, ‘Moses, make a god (ilāh) for us like their gods (āliha),’” and “Your god and Moses.’”[91]

As for the name “Allah,” its necessary definite article (lām) is a substitute for the initial glottal stop (hamza). This is why no one other than Allah was given this name—it has never existed in an indefinite form (i.e., without the integrated definite article al).[92] When Allah, the Most High, says in the Qur’an, “Do you know any other who merits His name?” it means, do you know of anything else called Allah? Do you know of any being who matches Him in creation or in being a necessary deity?[93]

Also, the fact that one word is derived from another does not necessitate that they have a shared meaning. The Arabs often coin different words from the same root to express distinct meanings. For example, they call a structure ḥaṣīn (fortified) and a woman ḥaṣān (virtuous or married)—both coming from the root ḥaṣāna (protection). Similarly, a tree is called a razīn (stable), a woman razān (composed), both derived from protectiveness (ḥaṣāna) and solemnity (razāna), respectively. [A figure of speech from pre-Islam Arabs] illustrates this: They falsely claim that the star al-ʿAyyūq (Capella, which literally means “the hinderer”) prevents or stops the al-Dabrān (Aldebaran) from moving—as if al-Dabrān is leading a dowry made of twenty small stars to ask for the hand of al-Thurayyā (Pleiades). According to the metaphor, Aldebaran endlessly chases the Pleiades and “proposes” to it. Aldebaran, as such, is hindered or halted. This group of twenty stars is called al-Qilāṣ, meaning the constricted ones.

About this, a poet writes,

The chained have fulfilled their obligation,

In the same way, the “camel driver” of the Qilāṣ stars did.

Based on that, it is not rejected that “Allah” is derived from divinity (ulūhiyya), a doctrine that the majority uphold.[94] It is said to derive from aliha, meaning to flee to take refuge. Allah, the Most High, is the refuge to which everything turns. This opinion is narrated from Ibn ʿAbbās (d. 68/688). Otherwise, it is derived from aliha, if one is baffled and perplexed. The reason is that minds are baffled in the seas of the grandiose of Allah, the Most Transcendent, and how thoughts cannot encompass Him and how limitless He is. There are other opinions on its derivation.[95]

20. Distinct features of the proper noun “Allah” which do not apply to other names of Allah

Among the unique characteristics of the name “Allah,” the Most High, is that it is a proper noun that is specific to Him—unlike all His other names, which describe His attributes. All of His names refer to Him, but they are not used to refer to each other. As the Qur’an says, “The Most Excellent Names belong to Allah.”[96] Other names—even if unused—can be imagined as names for others. But the name “Allah” needs the definite article al (the alif and the lām) instead of the glottal stop (hamza),[97] and this feature is not found in any other name. It was also granted a specific style of oath-taking that is not given to any of Allah’s other names or to any of His creations—for example, in saying “ta-Allāh la-ʾafʿalann” (By Allah, I will do…). This is taken as proof of the name’s virtue.[98] Another unique aspect is that the name “Allah” combines the vocative particle yāʾ (a word or particle used to address or call someone) and the definite article lām, something that does not occur except when poetically required.[99] Additionally, the initial alif of “Allah” is omitted in writing. One reason for this is to exalt Allah above looking similar to Allāt [the name of the pre-Islamic idol], whether in a vocal pause (waqf) or script. This is especially the case when Allāt is written with a hāʾ. However, the standard explanation is that it is omitted due to the frequency of its use.

Given the unique features mentioned—and others—of this majestic name,[100] some have deemed it as Allah’s Most Majestic Name (ism Allāh al-aʾẓam). Many experts from different sciences have spoken about this name, the sum of which cannot be contained in entire volumes of books.

No soul reaches an opinion,

Except there is yet a greater one to be discovered!

The Master Abū Isḥāq al-Isfārīnī (d. 418/1027) said, “This name signifies an essence associated with the attributes of majesty, with a power that befits originating its contingent attachments, with knowledge that encompasses all objects of knowledge (maʿlūmāt), and a will operating on willed matters. To Him is the command and prohibition. Worship is not valid except of Him, and has an attribute that is necessary for Him, which is His exclusiveness (ikhtiṣāṣiyya) in His being in a way that does not occupy space or locus.”

26. The names of Allah are ordained

Judge Abū Bakr [al-Bāqillānī] said,

Know that Allah’s names are ordained (tawqīfiyya) and are not a product of analogous reasoning (qiyās) or rational consideration. Many groups have erred in this regard. With Allah’s aid, we shall successfully clarify the essence of the matter. We say the source of Allah’s names is ordainment (tawqīf). Tawqīf means the receipt of permission from Allah, Most High. Anything that is related to be left unrestricted, we leave unrestricted. What the Sacred Law (sharʿ) prohibits, we prohibit. For anything without established permission or prohibition, we do not judge it as either admissible or unlawful, permissible or prohibited, since these are two rulings that cannot be adjudged except via the sharʿ. This approach is precisely the approach to be taken towards issuing rulings before the advent of revelation (sharʿ). Additionally, a definitive (qaṭʿī) narration is not required to establish the permissibility of a label; a fairly authentic (ṣaḥiḥ) report suffices.[101]

He added at the end of his discussion,

What should be expanded on is that any deluding expression, the apparent meaning of which implies something that the Lord, Most High, is sanctified above, is not permissible to use as a label except with a sharʿ based evidence. Similarly, whatever term is established as prohibited, we prohibit it. If there is neither permission nor prohibition, we suspend judgment about it (tawaqqafnā fīh).[102]

This is his upheld opinion, which is chosen when disagreement arises.

Some maintain that any name that alludes to a meaning befitting Allah’s majesty and attributes is permissible without requiring ordainment (bilā tawqīf). The reason is that Allah’s names and attributes are referenced in Persian, Turkish, and all languages, none of which are mentioned in the Qur’an and hadith. Despite this, the consensus among Muslims is that it is permissible to use these names for Allah. Additionally, Allah says, “The Most Excellent Names belong to Allah, use them to supplicate to Him.”[103] The suitability of a name depends on whether it reflects praiseworthy attributes and majestic descriptions.[104] Every name that conveys such meanings is considered appropriate and can be used to refer to Allah, in accordance with these proofs. This is because words only have value insofar as they convey accurate meanings—if the meaning is accurate, then using the term is permissible.

There is also a third perspective on this topic, put forward by Imam al-Ghazālī (may Allah grant him mercy). He argued that ascribing a name to Allah is only permissible through ordainment, while describing His attributes does not require such ordainment. In this view, there is a clear distinction between Allah’s names and His attributes. He said,

My name is Muḥammad. Yours is Abū Bakr. This pertains to the subject of names. In contrast, attributes, such as describing a human as tall or intelligent, and so on… It is because [deviating from] one’s given name is bad manners. It is more deservingly so with respect to Allah. However, regarding our attributes, it is permissible to refer to them using different wordings and expressions without restriction. The same principle applies to the Creator, the Most High.[105]

27. Does lā negate eternally or temporarily?

Some honorable scholars suggested that the word “no” (lā) implies a permanent, eternal negation, while “will not” (lan) indicates a temporary one. Conversely, others, like the Muʿtazila, argued that lan signifies permanent negation. They used this principle to deny the possibility of seeing Allah (known as the Beatific Vision or ruʾya) in the Hereafter. They based this on the verse where the Most High says to Moses, “You will never see Me” (Qur’an 7:143).[106] This view was reported by Imam al-Juwaynī, the “Imam of the Two Sanctuaries,” in his work al-Shāmil.[107] Their reasoning was challenged using another verse in which Allah, the Most High, says to the Jews, “Then you should long for death if your claim is true. But they will never long for it.”[108] Then, Allah states that the disbelievers in general will long for death in the Hereafter, as they say, “Would it had been the ending strike!,”[109] meaning death.[110]

I would say that the correct view is that both lā and lan are used to negate future tense verbs. Whether that negation is eternal or temporary is determined by the external context, not by the words themselves. For example, the Muʿtazila cite the following words of the Most High as proof that lan always means a permanent, eternal denial: “If you cannot do this—and you never will (lan tafʿalu)”[111] and “They will not create (lan yakhluqa) a fly.”[112] But this can be rebutted by pointing to other verses, such as: “Neither slumber nor sleep overtakes Him (lā taʾkhudhuh),” “it does not weary Him (lā yaʾūduh) to preserve them both,”[113] and similar verses which use lā to express eternality, not lan. This demonstrates that both lā and lan are used for mere negation, while establishing permanency or otherwise depends on what other evidence in the text indicates.

Al-Zamakhsharī, being a scholar from the Muʿtazila school of thought, stated in his book al-Unmūdhaj that lan signifies a permanent or eternal negation. Yet in another of his works, al-Kashshāf, he said that lan simply expressed negation. Both claims are baseless, as we’ve already discussed. If lan were used to express eternal negation, the subject of its negation would not be limited to a day—like in the verse, “I will not talk (lan ukalima) to a human today.”[114] Clearly, the denial here only applies for one day, not forever. Additionally, in the verse, “But they will never long for it (lan yatamannawnah) [i.e., death],”[115] adding the word “forever” (abadan) would be unnecessary. In Arabic, unnecessary repetition (redundancy) is avoided, so this supports the idea that lan on its own does not always mean something eternal.

Al-Zamakhsharī stated that lā does not signify eternal negation. Instead, he said that unlike lan, lā simply negates a future-tense verb [that has a prefix attached directly to it to indicate the near future, otherwise known as the particle of futurity or ḥarf tanfīs],[116] unlike lan. Although this aligns with the famous grammarian Sībawayh’s explanation of the phrase “will do” (sayafʿal), al-Zamakhsharī’s intention was to support the principle—held by the Muʿtazila—about seeing Allah in the Hereafter, as previously mentioned. The literal reading of the verse [Qur’an 7:143] negates the occurrence of the Beatific Vision either in response to the request or within the context of this worldly life. The question only addressed this point, and the answer corresponds to the question. Consequently, it did not ascertain negation for eternity but shifted focus to the manifestation of the signs onto the mountain.[117]

28. Lan signifies negation in the near future and lā negates what is in the distant future

Some scholars of eloquence (ʿilm al-bayān) have said that lan signifies negation in the near future, while lā negates what is in the distant future. This view contradicts that of al-Zamakhsharī. These scholars argued that the way we speak reflects the meanings of our words, and that when pronouncing the alif of lā, the elongated alif takes more breath than lan, which they believe implies an additional temporal distance. Their rationale is that the extended vowel sound [in lā] suggests a longer period.

The same assertion was made about the word “then” (thumma). It was suggested that because thumma contains more phonetic components than the single letter fāʾ (which also means “then”), this warrants a greater sense of detail or extended time. The idea being that a greater number of letters indicates a plurality of meanings. Rhetorical scholars used this reasoning to interpret the two verses: “But they will never long for it (lan yatamannawh) [i.e., death]” and “They would never hope (lā yatamannawnah) for it [i.e., death],” each according to one of these two linguistic approaches.[118]

From the perspective of eloquence, the second opinion on “lā yatamannawnah” follows the condition mentioned in Allah’s words: “If you truly claim that out of all people you alone are friends of God, then you should be hoping for death.”[119]

A conditional particle (ḥarf al-sharṭ) applies across all verb tenses. Therefore, the response uses lā to cover the full scope of what happens if the condition is met (sing. jawāb al-sharṭ). This means that whenever they make this claim—at any given time—then tell them, “Then you should be hoping for death.” The phrase “They would never hope for it (lā yatamannawnah)” comes after Allah’s words, “Say, ‘If the last home with God is to be for you alone and no one else,’” meaning if the homecoming in the afterlife is necessarily yours, then wish for death now to expedite being in the Abode of Honor (dār al-karāma), which Allah prepared for His friends and loved ones. Accordingly, Allah’s saying, the Most High, came to be, “You will never see Me (lan tarānī).”

29. The difference between the two particles of negation

Let anyone knowledgeable about the meanings of words remember what I confirmed here about the two particles of negation: lan and lā. What remains now is to address the negative particle lam. While these particles of negation are often called “sisters” because they both serve the purpose of negation, they are, however, more like “half-sisters” (ʿallāt)—distinguished by their degree of negation, determined by specific causes and contextual clues.

Sībawayh explained that lam is a negative particle (ḥarf nafy) used with verbs in the morphological pattern of fa-ʿa-la (the simple past), lan is used to negate verbs in the future form of sa-ya-f-ʿal, and lā is used with the present tense form ya-f-ʿal. What he means is that lā is conventionally used to negate the future-tense verb unrestrictedly and that it may be used to negate the past tense. For example: (1) In cases of repetition, as in His saying: “He neither believed nor prayed (fa lā ṣaddaqa wa lā ṣallā)”;[120] (2) In cases of placing importance, as in: “Yet he has not attempted the steep path (fa lā aqtaḥama al-ʿaqaba)”;[121] (3) In supplication, like the Prophet’s words, Allah’s peace and blessing be upon him: “May you never be able (lā astaṭaʿt)!”;[122] (4) In the wording of supplications, like the Prophet’s saying, “May your age [not] extend long ([lā kaburat sinnuk])”; and (5) In fluctuations in meaning between supplication and negation, like his saying “[Maybe] he neither fasted nor broke his fast (lā ṣām wa lā afṭar),”[123] which alludes to whoever fasts continuously. Lan, as previously mentioned, is used to negate the future verb.

And may Allah’s peace be on our master and leader Muhammad, the one whose messengership is mercy and whose words are wisdom, his companions, his entire family, and praise be to Allah, the Lord of the worlds.

Notes

[1] Qur’an 47:19.

[2] Muḥammad al-Ṭāhir Ibn ʿAshūr, al-Taḥrīr wal-tanwīr, 30 vols. (al-Dār al-Tūnusiyya li-l-Nashr, 1884), 26:104–5.

[3] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 35.

[4] Abū Nuʿaym al-Aṣfahānī, Ḥilyat al-awliyāʾ wa ṭabaqāt al-aṣfiyāʾ, 19 vols. (Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, n.d.), 7:17.

[5] Qur’an 15:92–93.

[6] Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn ʿUmar al-Qurṭubī, al-Jāmiʿ li-aḥkām al-Qurʾān, ed. ʿAbd al-Muḥsin al-Turkī, 24 vols. (Muʾsassat al-Risāla, 2006), 12:258.

[7] Aḥmad al-Dardīr, Sharḥ al-kharīda al-bahiyya, ed. ʿAbd al-Salām Shannār (Dār al-Bayrūtī, n.d.) 168–69.

[8] For a detailed exposition of how the Statement of Faith encompasses the principal tenets of belief, see Abū al-Ḥasan ibn Masʿūd al-Yūsī, Mashrab al-ʿāmm wa-l-khāṣṣ min kalimat al-ikhlāṣ, ed. Ḥamīd al-Yūsī, 2 vols. (Dār al-Rashād al-Ḥadītha, 2019), 1:527–32

[9] Abū ʿAbdullāh al-Sanūsī, “Umm al-barāhīn,” in Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī ʿalā umm al-barāhīn, ed ʿAbd al-Laṭīf ʿAbd al-Raḥmān (Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2017), 254–55.

[10] Al-Sanūsī, Umm al-barāhīn, 300–01.

[11] Al-Sanūsī, Umm al-barāhīn, 301.

[12] These sections are 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 26, 27, 28, and 29.

[13] Al-Sanūsī, Umm al-barāhīn, 309–10.

[14] Tāj al-Dīn al-Subkī, Ṭabaqāt al-Shāfiʿiyya al-kubrā, eds. Maḥmoud al-Tanāḥī and ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ El-Ḥilw, 10 vols. (ʿIsā al-Ḥalabī, 1964), 1:38–41. However, al-Subkī contested two of ʿIkrima’s interpretations, disagreeing with him on their indications to the testimony of faith.

[15] Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ wa miṣbāḥ al-arwāḥ (Maṭbaʿat al-Saʿāda, n.d.), 67–73.

[16] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 3265. Similar reports attribute this interpretation to some of the companions, including ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb and ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib.

[17] Al-Subkī, Ṭabaqāt al-Shāfiʿiyya, 1:39.

[18] Al-Dardīr, Sharḥ al-kharīda, 170.

[19] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 3.

[20] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 3. See also, al-Yūsī, Mashrab al-ʿāmm wa-l-khāṣṣ, 2:10–14.

[21] Al-Muwaṭṭaʾ, no. 726.

[22] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 3585.

[23] Sunan al-Nasāʾī al-kubrā, nos. 10602 and 10913. Scholars have disputed the authenticity of this hadith. However, al-Ḥākim and Ibn Ḥajar al-ʿAsqalānī deemed it authentic.

[24] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 3383.

[25] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 536. He stated that it is a gharīb hadith whose chain of transmission is not strong.

[26] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 28.

[27] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 45.

[28] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 305.

[29] Qur’an 37:143–44.

[30] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 63–4.

[31] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 3293; Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 2691.

[32] Musnad al-Bazzār, no. 8292.

[33] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 3590.

[34] Qur’an 3:18.

[35] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 64.

[36] Qur’an 25:43.

[37] Qur’an 36:60.

[38] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 2887.

[39] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 17–18.

[40] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 18–19.

[41] Muḥammad ibn ʿAlī ibn Yūsuf al-Jazarī, al-Nashr fī al-qirāʾāt al-ʿashr, ed. al-Sālim al-Jakanī, 6 vols. (Mujammaʿ al-Malik Fahd li-Ṭibāʿat al-Muṣḥaf al-Sharīf, 2013), 3:846–48.

[42] Abū Bakr Aḥmad ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn Mihrān, Risālat al-maddāt, ed. Ayman Suwaid (Dār al-Ghawthānī lil-Dirāsāt al-Qurʾāniyya, 2018 ), 35.

[43] Abū Zakariyyā Yaḥyā ibn Sharaf al-Nawawī, al-Adhkār min kalām sayyid al-abrār (Dār al-Minhāj, 2005), 43–44.

[44] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 306.

[45] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 307. The full hadith is mentioned below in the section “Salvation and intercession in the afterlife.”

[46] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 307.

[47] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 2946.

[48] Qur’an 112:1.

[49] Qur’an 2:221.

[50] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 55–56.

[51] Sunan Ibn Māja, no. 3796.

[52] Ṣahīḥ Muslim, no. 26.

[53] Sunan Abī Dawūd, no. 3116.

[54] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 6423.

[55] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 99.

[56] Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, no. 3884.

[57] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 306.

[58] Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim, no. 917

[59] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 63.

[60] Al-Sanūsī, Umm al-barāhīn, 301-2.

[61] Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wāḥid ibn al-Humām, Fatḥ al-Qadīr, 2 vols. (Dār al-Fikr, n.d.), 2:104; Abū Bakr ibn al-ʿArabī, al-Masālik fī sharḥ Muwaṭṭaʾ Mālik, ed. Ḥāmid al-Maḥallāwī, 6 vols. (Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 2013), 3:520; Yaḥyā ibn Sharaf al-Nawawī, Rawḍat al-ṭālibīn, ed. Zuhayr Shāwīsh, 12 vols. (al-Maktab al-Islāmī, 1991), 2:138; Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Ibn Mufliḥ al-Maqdisī, al-Furūʿ, ed. ʿAbdullāh al-Turkī, 12 vols. (Muʾassasat al-Risāla, 2003), 3:383.

[62] Jāmiʿ al-Tirmidhī, no. 2639.

[63] Al-Sakandarī, Miftāḥ al-falāḥ, 44–45.

[64] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 306. He is likely referring to al-Mallawī’s gloss on al-Qayrawānī’s commentary on al-Sanūsī’s Umm al-barāhīn.

[65] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 308.

[66] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 318–19.

[67] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 318.

[68] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 321.

[69] Al-Dasūqī, Ḥāshiyat al-Dasūqī, 321.

[70] We could not locate this quote in Ibn Taghrībirdī’s biographical work, al-Manhal al-ṣāfī wa-l-mustawfī baʿd al-wāfī. However, some editors of al-Zarkashī’s works have attributed it to the original manuscript of the work. See, for example, Badr al-Dīn al-Zarkashī, Salāsil al-dhahab, ed. Muḥammad al-Shinqīṭī (N.p., 2002), 53.